Here’s what we learnt

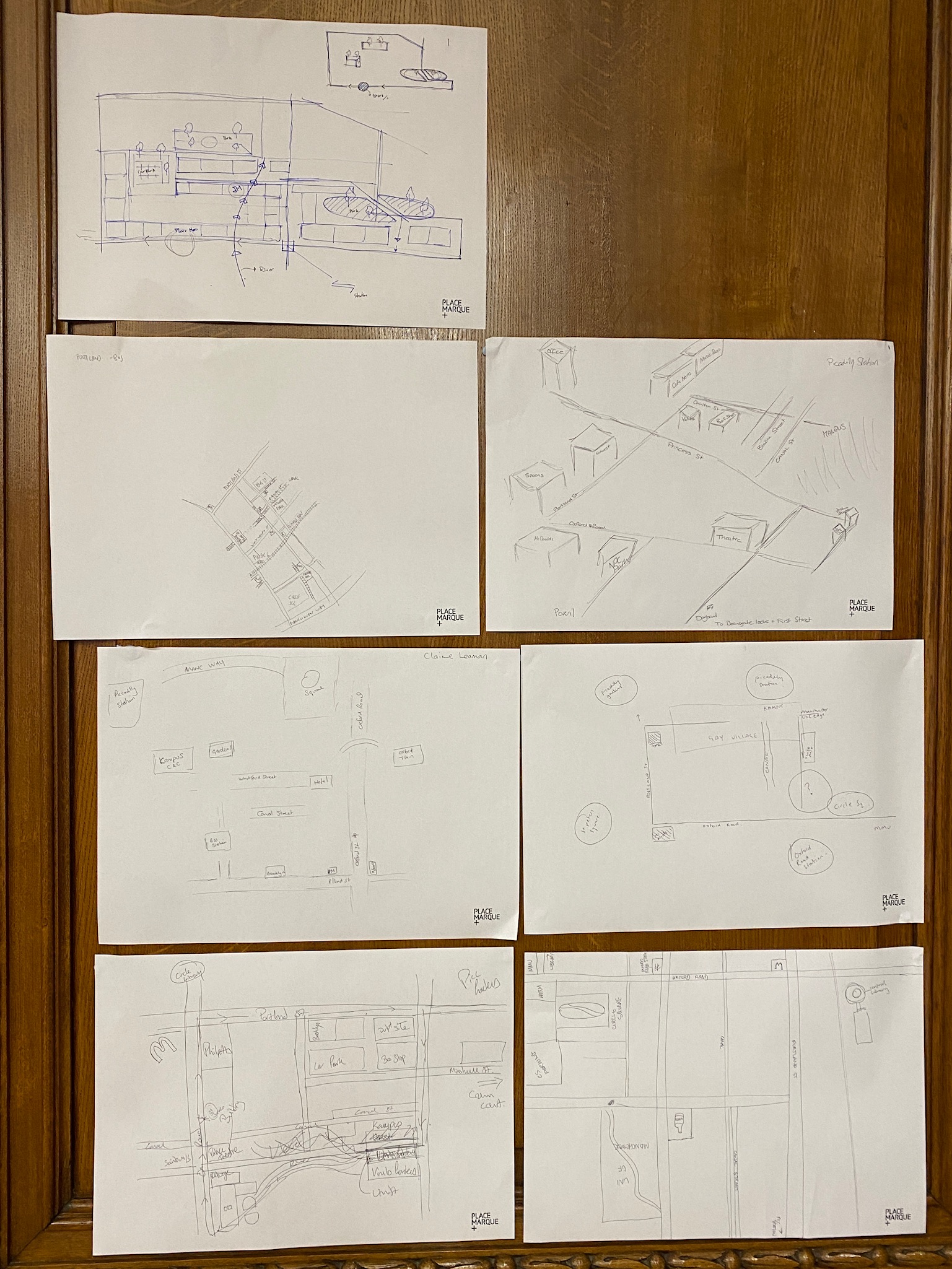

This time last week, we brought together a bunch of built environment professionals for a “mental mapping” exercise of Manchester city centre. We would usually do this kind of thing when we begin work on a wayfinding strategy as a way of understanding how the people who use that space, whether it’s a university estate or a town centre, visualise it. It’s always an interesting exercise that tells us which parts of a place knit together, how people who already know the area find their way around it, and which places are often forgotten. A mental map is a very human exercise, where everyone puts north in a different place and their “heads up” direction varies. And we usually do this with ordinary people – not place professionals. Here’s what we learnt.

The Manchester property community is invested in the city and they navigate by current and recent development projects and landmark buildings, more than a lay person normally would. Architects and landscape architects think in 3D – there were some insightful sketches created in under 10 minutes.

Most people navigate at a human scale and according to well-known places, which is why directions are so often “turn left at the Old Crown pub”, rather than “turn left onto the A34”. It was apparent to everyone that, in this instance, Manchester’s public realm is hard to read. We picked a route covering what many might feel is a leftover area but has the potential to be a strong connecting point between Piccadilly and Oxford Road. There were a few natural navigational clues, but we were also reliant on the signage. Unfortunately, the wayfinding signage in Manchester is often still very car-centric (even the signs aimed at pedestrians) and directs everyone along the main thoroughfares when there are straighter and more attractive routes for people walking or cycling. Finding those routes and making your way, say from Oxford Road to Piccadilly Station away from the busy thoroughfares and via the green spaces at Circle Square and Vimto Park, takes local knowledge.

The conversation as we walked our route was, as predicted, about the built environment around us. Manchester is full of waterways, yet they are often hidden and people are directed away from them due to safety concerns. In our view, Manchester’s “blue ways” should become a far greater park of the city’s visible infrastructure to encourage more exploration and active travel. We also talked about how quickly the character of a place changes: turn a corner and you find yourself in a completely different environment. This prompted some interesting reflections on how important it is that placemakers take more time to consider the places next door and how they weave together for better connectivity. We can all influence this: landlords, local authorities, estates and developers can all think a little more carefully about the space beyond their own space. The visitor doesn’t care whose it is; their experience is what matters.

Maintenance was a consistent part of the discussion, as it always seems to be with built environment professionals in the summer. We spend our holidays in attractive European cities and on our return to Manchester we are taken by how grubby it is. Dirty pavements, damaged street furniture, signage that needs a clean, broken lighting. Maintenance is always a consideration at the design and procurement stage, yet seems to slip once a place becomes used. Cleanliness is a small but important thing for people’s enjoyment of spaces, leading to improved safety and more footfall. And it always crops up when we do a mental mapping exercise, whether that’s with built environment professionals or with ordinary everyday people.

Our final point was about digital mapping. Google maps (and equivalents) has become the go-to tool for people finding their way across a city. You can choose from routes for cars, cyclists and pedestrians; fastest route or shortest. When will there be an option for the “most pleasant” route?