Inclusivity at the heart of wayfinding

This week is National Inclusion Week in the UK.

Not another awareness week, I hear you groan.

But wait, this is actually one of the most important, in fact. Particularly when it comes to design.

Our central principle

At Placemarque, the number one principle that guides all our work is:

Designing to meet the needs of all users

As placemakers we have a responsibility to make sure that the places we help shape will work for everyone. But over the years, our grasp of how we’ll deliver on this principle has evolved.

Back when Placemarque was founded in 2000, the industry’s understanding (as well as society’s at large) was that additional needs extended to those with a physical disability such as wheelchair users, or those with a visual impairment.

These specific needs remain very much central to our design process, and indeed, much still needs to be done to create places that are genuinely DDA compliant.

That said, when we consider how to achieve inclusivity and the needs of all users today, the conversation has moved on significantly. Not all disabilities are seen. Designers must, rightly, also consider people with Alzheimer’s, dementia and other neurodiverse needs.

A changing landscape of unseen needs

One of the main reasons that the UK won its bid to host the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games was the committee’s vision for how the event would help to address inequalities and deliver inclusivity, both in the built environment and through its legacy.

Key to the long-term ambitions of the London Legacy Development Corporation (LLDC), which was established in 2012, was to “support and promote the aim of convergence”. The convergence agenda referred to the vision that within 20 years the residents of host boroughs “will enjoy the same social and economic changes as their neighbours across London.”

As part of this vision, a series of good practice procurement and design standards were set out, for future developments at the park to follow. Fast forward a decade and it’s time for a refresh. The conversation has moved on.

In this changing landscape we are all more aware of the wide-ranging needs – often unseen – that exist. And that requires a fresh response in the way we plan, design and deliver new places and spaces.

Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park

We’ve been appointed by LLDC to revisit its Park Wayfinding Strategy, a document that was prepared after the 2012 Olympic and Paralympic Games but prior to the reopening of the park.

The park has evolved and become more established, in some ways, differently to what was envisaged at the time of the strategy.

Our work at East Bank has highlighted the complexity of the many different destinations and users, and the many different needs that exist for those users. And that’s just in one small section of the wider park!

The latest project to refresh the wayfinding strategy will need to consider the role of wayfinding in delivering truly accessible places and set out design principles to guide future development across the park.

Designing for inclusivity

What is the key to designing for inclusivity?

How do we translate an understanding and appreciation for society’s wider needs in the designs we produce?

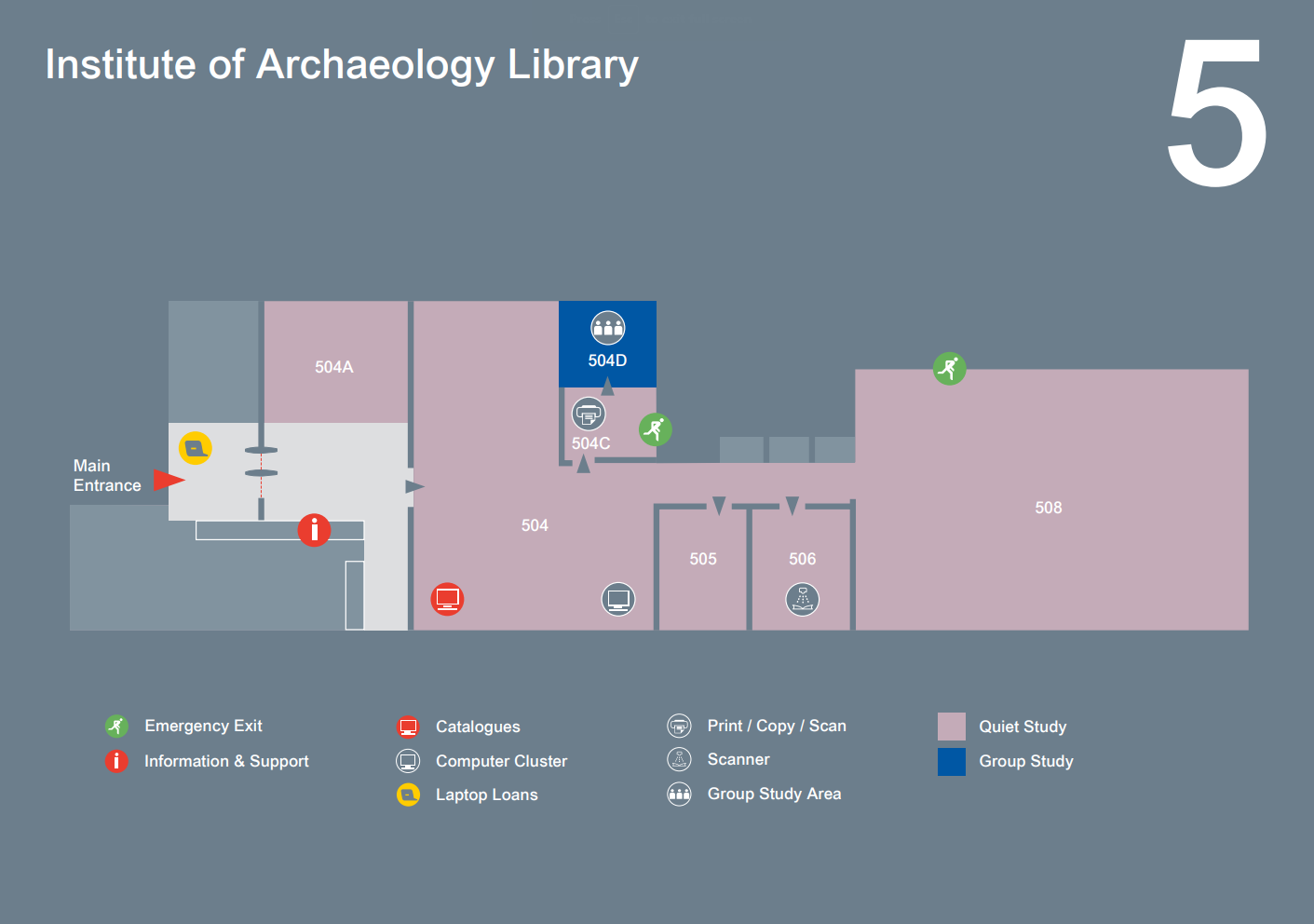

Part of the way that we ensure inclusivity in our designs is by striving to make our designs as simple as possible.

But don’t be deceived. A lot of work and thinking goes into translating a complex three-dimensional place into a simple, 2D graphic that can be readily understood by every user.

With every project, we task ourselves with asking if each piece of information is essential for the graphic to be understood. If it isn’t, it doesn’t make the cut.

Designing for dementia is actually good design. Good information design is about distilling something down to its basic facts. Designing for inclusivity doesn’t mean sacrificing good design. It’s the embodiment of good design.

“Good information design is about distilling something down to its basic facts. Designing for inclusivity doesn’t mean sacrificing good design. It’s the embodiment of good design.”

Guy Warren, Design Director

Wayfinding is set apart from other aspects of the built environment because beyond designing the object itself to be accessible (just as you do for a building or the public realm) there is also information that needs to be conveyed in an accessible way.

“Wayfinding is not just about accessibility; it’s about conveying information.”

Guy Warren, Design Director

There is a learning process that everyone goes through when they engage with wayfinding signage. Where am I on this map? What does my destination look like? How am I going to translate this graphic representation into real, on the ground directions?

If the information displayed becomes too complicated, it will be too hard to understand. We work hard to make that learning process much easier and quicker for all users.

The inherent challenge with designing for all

There are other things to consider in our designs.

High contrast colours are helpful for visually impaired users, but the wrong colours will cause problems for the colourblind.

Large monoliths help to create space and make information legible but could be more readily used by offenders to hide behind, making places less safe, particularly for women and girls.

Whether it’s minimising the amount of text on a graphic to help someone with dyslexia, or providing tactile surfaces to guide users, there are 101 different ways that we can incorporate inclusivity into our designs.

You can easily see the inherent challenge with designing for all: where we used to cater for two or three particular needs, there are now innumerable legitimate needs to consider.

Understanding accessibility issues in this broader way naturally means there is a more diverse set of needs that need to be taken into account in design.

Finding the right balance

There are no prescriptive rules to follow when designing for inclusive spaces

The key is carrying out the right research to understand users’ experiences, where they want to go, and working hard to strike the right balance between potentially competing needs.

When you design for those with the greatest need, you’re also designing for those without additional needs. After all, no one ever complained that something was too easy to understand.

In this changing landscape, we’re constantly striving to meet and improve on best practice and to work with others in the built environment to design places that meet everyone’s needs.

We can help you think through important user needs and create welcoming and friendly spaces that encourage visitors to stay a little longer and explore a little further. Get in touch with us today.